When a video game opens with a Bible quote, you know you’re in for something special.

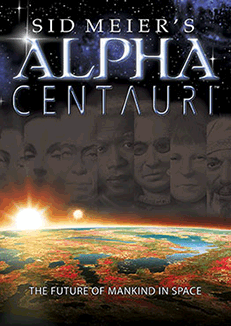

Sid Meir’s Alpha Centauri, released in 1999 by Firaxis Games, has something of a reputation in the gaming community. It comes from the same developers as the venerable Civilization series, to the point of using an improved version of Cvilization II’s game engine. But the experience it offered was something entirely different. Instead of taking historical civilizations and guiding them from the dawn of man to the modern age, Alpha Centauri takes some of humankind’s most prominent ideologies and puts them to the test colonizing an alien world. With hard science fiction, three-dimensional characterization and a climactic premise, Alpha Centauri is widely considered to be one of the most well-written science fiction games ever made.

For non-gamers, I should point out that this is rather an impressive claim to fame for a strategy game. Especially one that belongs to the ‘4X’ subgenre – shorthand for ‘Explore, Expand, Exploit, Exterminate’. These sorts of games tend to be truly strategic in nature, as opposed to the more tactical scale many adopt. Where some strategy games have you command an army or a base, 4X games often give you the reigns of an entire civilization. Empires may rise and fall by your hand, and your actions affect millions if not billions of lives. Sheer scale often means that characters will be mostly limited to other leaders you interact with, and narrative consists more of events playing out organically instead of being pre-scripted.

For a 4X game like Alpha Centauri to excel in its writing means that it’s able to overcome a lot of the limitations of its genre. And considering my motivation to check out this game was on account of the writing, I’d love to walk you through just how it accomplishes this feat.

Therefore the Lord God Sent Him Forth From the Garden of Eden

The game’s intro video is one of the most impactful I’ve ever seen. It opens with the aforementioned Bible quote, which you quickly come to realize perfectly sums up the opening premise. As the music starts up, we see what has become of Earth in the new millennium. War. Unrest. Poverty. Pollution. Nuclear war. It’s clear that civilization is on its last legs. Then the music settles, and we’re introduced to a last cause for hope. Images of space shuttle launches are overlaid atop the people of Earth, showing just how much is riding on the promises of space travel. And sure enough, as the music swells, we see the last hope for humanity: the United Nations Starship Unity, an ark to ferry humanity to a new world.

The narrator takes over, and tells us what we already suspected. Earth is collapsing. But in a last-ditch effort to avoid extinction, the UN launches the Unity and several thousand colonists to Chiron, an Earthlike planet spotted in the Alpha Centauri system. Against all odds, the Unity makes it to the new star system, before it is crippled by a reactor malfunction. Tensions flare aboard the crew, and when it comes time to make a desperate planetfall the survivors split into groups headed by different members of the command crew. The colony pods are released, with seven reaching the surface of Chiron to begin colonization.

As the game proper starts, the misfortune of the colonists only grows. Chiron – or ‘Planet’ as it is more commonly referred to – is no paradise. While the nitrogenous soil is perfect for Earth plants with the right adjustments, the atmosphere is too light on oxygen and heavy on carbon dioxide for humans to breathe it naturally. The native wildlife is similarly hostile, from fields of xenofungus clogging the landscape to aggressive wildlife launching frequent attacks. The most common – and easily most horrific – predators are the mind worms, which use a psychic attack to paralyze their prey before implanting larvae into their brains. Every day on Planet will be a struggle for survival in the face of alien life. But perhaps the greatest danger will be far more human in nature.

To Believe What He Prefers to be True

The factions – and the people who lead them – are one of the greatest strengths of Alpha Centauri. Unlike the civilizations of the old Civilization games, they are not based on nationality or geography, but instead ideology. Each one encapsulates a worldview in some way inherited from Earth, pitting it against both the hostile lifeforms of Planet and opposing human factions. This is what makes Alpha Centauri such a standout among strategy games; it is, at its core, a climactic ideological battle that will determine the future of humanity in its darkest hour.

But what truly sells it is the clever way in which the game characterizes the factions and their leaders. Every time the player researches a technology, constructs a particular base facility for the first time, or completes a secret project (a powerful one-of-a-kind building much like the world wonders in Civilization), they are treated to a quote. Some of these are from literary sources, real or fictional, but the majority are from one of the faction leaders. These little snippets of information shine a great deal of light into the setting and its inhabitants. One of my personal favourites is the quote that comes from building the Recreation Commons base facility for the first time. In this quote, readable on the wiki page linked, we learn how members from several of the factions unwind in their spare time. A simple matter, but it tells us a lot about what everyday life is like for many of the colonists and how their cultures vary depending on their faction. It also hints at how Pravin Lal – head of the humanitarian Peacekeeper faction – views the authoritarian collectivism of Sheng-Ji Yang’s Human Hive. Other quotes vary wildly, discussing individual views, historical events, the application of certain technologies, and increasingly esoteric topics as scientific progress surpasses what was known on Earth.

The seven factions featured in the game are as follows:

- The Peacekeeping Forces, lead by Chief of Surgery Pravin Lal, are the last remnant of the UN, determined to uphold its humanitarian ideals. Although hindered by bureaucracy, they can support large and well-educated populations while wielding significant diplomatic weight.

- Gaia’s Stepdaughters, founded by Chief Botanist Deidre Sky, are committed environmentalists, driven by the desire to never let the environmental catastrophes of Earth be repeated. This does hurt their industrial output, and their pacifist nature similarly hinders their military. But they are also very efficient with the resources they use, and are so in tune with Planet’s ecosystems that they can capture native wildlife for their own use.

- The University of Planet was established by Chief Science Officer Prokhor Zakharov, and is dedicated to rational scientific inquiry. Naturally, they get some hefty research bonuses, but there is a darker side to their faction; their unetheical experimentation leads to internal discontent, and their academic openness leaves them vulnerable to infiltration and data theft.

- Morgan Industries – a major sponsor of the Unity project – was re-established after CEO Nwabudike Morgan stowed away on board. He views the colonization of Planet as an unprecedented economic opportunity, and fully intends to eventually privatize all human endeavor under his company. Morgan naturally gets an inherent bonus in the game’s energy-based economy, but the selfish nature of his faction leaves his military understaffed and his bases hard-pressed to support large populations.

- The Lord’s Believers are the flock of Psych Chaplain Miriam Godwinson, who preaches an evangelical brand of Christianity. They fight readily and ferociously in the defense of their faith, while gaining an infiltration bonus from their willingness to subvert the other, more secular factions. But their distrust of science puts them at a disadvantage in terms of research, and their view that Planet is their ‘promised land’ makes them prone to damaging its biosphere.

- The Spartan Federation are the forces of Security Chief Corazon Santiago, committed to survivalism, militarism and social Darwinism. It should come as no surprise that their military is the best-trained in the game, and their population the most disciplined. However, their myopic focus on their military tangibly hinders their internal economy, leaving them reliant on quality over quantity.

- Finally, the Human Hive is the brainchild of Executive Officer Sheng-Ji Yang, founded upon a curious blend of authoritarianism, collectivism and Eastern philosophy. Their underground bases give them a defensive advantage, while their brutal serfdom boosts industrial output and population growth. This comes at a cost, of course, as the lack of freedom and initiative all but kills their economic strength.

The factions are not just divided by ideology. The game also features a ‘social engineering’ system, determining a faction’s position on politics, economics, guiding values, and its vision of what future society will look like. There are three options for each, though each faction has a ‘preferred’ choice for one particular option along with a particular aversion for another. This leads to some natural enemies, such as the democracy-loving Peacekeeping Forces against the police state-loving Human Hive. It also allows you to adopt particular beliefs to curry favour with other factions. There’s a great deal of customization on the player’s behalf, allowing them to customize some of the finer points of each faction’s views.

This nuance extends to the faction leaders too, with each of them given a great deal of dimension through their various quotes. Others can be viewed very differently simply by considering their context. For example, Miriam Godwinson initially appears to be little more than a violent fundamentalist with an anti-intellectual streak. But her apprehension towards unchecked scientific advancement makes a little more sense given some of the technologies that emerge in the game. Just take a look at the videos that play if you build The Dream Twister, or The Self-Aware Colony. Another example is Pravin Lal, who gives the impression of a very reasonable leader dedicated to upholding the traditions of Earth. Fairly palatable to a modern player, considering that the other factions are racing off in wild ideological directions. But for all his liberal and humanitarian ideals, this ironically leaves him as one of the most conservative leaders as he clings to the memory of a dead planet. His quote for the Biomachinery technology also paints him in a very different light. Similarly, the quote that Prokhor Zakharov’s underling gives for Retroviral Engineering indicates that Zakharov – and possibly the University as a whole – is not as committed to academic transparency as they claim. This isn’t the only time Zakharov is depicted as hypocritical, dropping his coldly rational persona in the Temple of Planet base facility quote, while using some very religious terms to describe The Voice of Planet considering he is a committed atheist.

Bright Children of the Stars

Spoilers ahead! If you want to experience the end of the game for yourself, consider skipping this section.

What is the Voice of Planet, you may ask? Good question! As the game progresses and technology advances, it turns out that the xenofungus is more than just local greenery (or red-ery, I guess). It forms part of a natural neural network, periodically reaching the threshold of sentience every few million years. But this process is unable to sustain itself, triggering Planet-wide mass extinctions before returning to dormancy. And unfortunately for humanity, its disruption of planet’s biosphere means that one of these so-called Flowerings is rapidly approaching. It seems that they left one dying planet for another.

Hope is not lost, however. Humans eventually devise methods of not only communicating with Planet, but guiding it. Of all the victory conditions in the game – conquering the planet militarily, cornering the global energy market economically, or being elected Supreme Leader of Planet through diplomacy – Transcendence is by far the most final. Should the player complete the Ascent to Transcendence secret project before anyone else, their ideology will be written into mind of Planet itself, permanently enshrining it into the emerging consciousness. Moreover, the player’s colonists will use psionics to transcend their physical bodies, merging with Planet’s power to become living gods. Those from the surviving factions that failed aren’t left in the lurch, still welcomed into the collective consciousness or being provided physical forms to explore the universe with.

But even so, a faction completing Transcendence will mark the dawn of a new age for humanity. Where the bonuses of other secret projects are often described in basic, functional terms – ‘+2 minerals at every base’, ‘Labs output doubled at this base’, ‘Counts as a Command Center at every one of your bases’ – the description for the Ascent to Transcendence is poignant in its simplicity: ‘Completes the Transcendence sequence and ends the Human Era’.

So, who will win this grand clash of ideals? It depends on the player. You can win the game as any faction, or lose to a computer-controlled one. But if you piece together the various quotes, a ‘canon’ story starts to emerge. Godwinson’s quote for the Psi Gate base facility – attributed as her ‘last testament’ – implies that she eventually pulls an unintentional Jim Jones-style mass suicide trying to teleport back to Earth. Further quotes – particularly for the Headquarters and The Citizen’s Defense Force – imply that the Spartans fell to the Gaians and their trained mind worms. The University, too, is said to have clashed with the Gaians based on the Temple of Planet quote, but Zakharov’s continued contributions to the technology quotes after that implies that they at least survived. Yang and Morgan stp contributing to the quotes around the middle game with little fanfare, likely either defeated or having surrendered to others factions. Lal seems to hold out a little longer and have enough of an appreciation for Deidre’s ideology that the Peacekeepers could ally with the Gaians. But with so many quotes attributed to Deidre’s ‘Conversations with Planet’, it’s a safe bet to assume that she was the most attuned to Planet’s consciousness. Enough that she could quite conceivably have won the race to Transcendence. There’s a certain appropriateness to that; Deidre is an introverted person implied to understand plants better than people. In a way, nobody else but the most committed environmentalist would be more suited to hearing the Voice of Planet.

Layers Within Layers, Worlds Within Worlds

This is not the end of the story for Alpha Centauri. Later in 1999, Firaxis released an expansion pack for it called Alien Crossfire. The expansion features a number of mechanical improvements and new content, from new base facilities to new landmarks on the game map. But from the perspective of the game’s ideological smorgasbord, the juiciest addition are seven new factions. While their beliefs are a little more niche than the original seven, and the scarcity of new quotes don’t give them or their leaders quite the same level of dimension, they aren’t without note.

- The Free Drones, led by Foreman Domai (formerly Director of Planetside Mining Ops Arthur Donaldson), are a more democratic take on collectivism than the Human Hive. Their society is a gritty workingman’s paradise, complete with a powerful industry and even a chance for rebelling bases to join them. But their emphasis on hard work over theoretical sciences severely hinders their research capabilities.

- The Data Angels, led by Sinder Roze (the online handle for Network Administrator Asa Wright), are an libertarian and almost outright anarchist group led by computer hackers. Their espionage capabilities are second to none, though their free-spirited nature makes them difficult to manage.

- The Nautilus Pirates, ‘led’ (for lack of a better term) by Astrogator Ulrik Svensgaard, are an even more anarchic group that focus largely on the thrill of exploration and plunder. They’re one of the more mechanically unique classes, as they are the only ones who start the game at sea. Coupled with a raft (pun intended) of sea-based bonuses, they are undisputed rules of the waves… which is just as well, since their hedonistic society would barely function without them.

- The Cybernetic Consciousness, led by Aki Zeta-5 (once Subroutine Specialist Annikki Luttinen), are what it says on the tin: a collective of cyborgs who have rejected human emotion in favour of dispassionate logic. All well and good for research and efficiency, but this doesn’t do wonders for population growth.

- The Cult of Planet, led by Cha Dawn, are possibly the most eerie of the human factions. Unlike most of the other faction leaders, Dawn is too young to have arrived on the Unity. Instead, he was discovered as a baby in the wilderness, completely unharmed by the toxic atmosphere and deadly wildlife. This led to a cult springing up around Dawn and his apparent connection to Planet, which his followers worship with a fanaticism greater than even the Lord Believer’s. Their driving ideology is a brand of environmentalism even more extreme than that of the Gaians, crossing over intro voluntary extinction territory. They wish to preserve Planet’s natural state, and will not hesitate to destroy anyone who violates it. Which is to say… everyone. Possibly including themselves. They have very little industrial or economic power, but are extremely adept at capturing native wildlife for their own gain.

Note that I said ‘of the human factions’. That’s because the other two factions introduced in Alien Crossfire are… well, alien.

There was evidence in the original game that intelligent life was out there. Alien monoliths peppered the surface of Planet, alongside artifacts that could be retrieved and studied. Aside from providing some gameplay bonuses, the exact nature of these was largely a mystery. But as we learn in Alien Crossfire, Chiron was one of numerous Manifolds – a series of experiments in creating a planetwide nervous system – created by an alien species known as the Progenitors in the distant past. And not only are the Progenitors alive and well, but they too are in the midst of a pitched ideological battle of their own.

Compared to the humans, the Progenitor struggle is comparatively simple. On one side are the the Manifold Usurpers, who wish to seize the Manifolds to turn themselves into living gods. On the other are the Manifold Caretakers, who wish to uphold tradition and leave the Manifolds alone – especially in the wake of the Tau Ceti Flowering. Details are light in the game on what happened in Tau Ceti, but supplementary materials indicate that the Usurpers attempted Transcendence in a way that backfired horribly, killing billions of the planet’s inhabitants in the process. The Usurpers are determined to try again on Chiron, considering the innumerable rewards of godhood to outweigh the massive risk, while the Caretakers will stop anyone – be they Progenitor or human – from repeating the tragedy.

The two Progenitor factions share a lot of the same technology tree as humans, which is dismissed as them recovering lost knowledge post-crash. They do have some unique units and bonuses, but this actually leaves them very overpowered. The main downside for them gameplay-wise is that diplomacy is all but impossible. The two Progenitor factions are automatically hostile to each other, and have little in the way of meaningful dealings with humanity, who they consider to be little more than animals. The Progenitors are also not covered by the UN Charter, meaning that atrocities committed against them by humans – such as using nerve gas or nuclear weapons – are completely fair game, with none of the diplomatic penalties that would come from doing the same against another human faction.

But storywise, the inclusion of the Progenitors is still quite intriguing. You’ve essentially got another ideological struggle for a species’ future crashing into an existing one: two plots that could each support an entire game. While not quite as nuanced as the human one, the Progenitor story is still compelling once you have all the information. You have half a civilization chasing godhood at an increasingly heavy cost, and the other trying to uphold tradition to survive even if it means stagnating. You can even draw a lot of comparisons between the Progenitors and humans, which is ironic given the low opinion the former holds of the latter. The Usurpers especially resemble humanity more than they ever would admit, with a level of militarism that not unlike the Spartans and a willingness to challenge tradition that the University would approve of. The Caretakers, on the other hand, have a respect for Planet’s native life that the Gaiains would likely appreciate, along with a dedication to tradition that brings to mind the Believers or possibly even the Peacekeepers. Coupled with the fact that the Progenitors are fleeing a dying world from a tragedy of their own making only makes the parallels all the more evident, and the rich tapestry of Alpha Centauri all the more colourful.

In the Twilight of Earth’s Great Civilizations

While Alpha Centauri never received any further expansion packs or sequels, Firaxis did make a spiritual successor. Civilization: Beyond Earth was released in 2014, drawing heavily from the Civilization V game engine just as Alpha Centauri drew from Civlization II so many years before. The reviews of Beyond Earth were fairly positive, and it introduced a lot of interesting ideas that hadn’t been seen before in the Civilization series. Every time you built a new building for the first time, you’re given a decision to customize it in one of two ways; for example, you could designate your Old Earth Relics as public spaces to bolster their cultural output, or treat them as solemn shrines to cut down on maintenance costs. The linear tech tree typical of Civilization games (and, indeed, Alpha Centauri) was replaced by a technology web, offering nonlinear paths to different scientific advancements. Even the beginning of the game was overhauled to be highly customizable, as instead of just choosing your faction you now also choose your colonists (bolstering certain resource outputs in your bases), spacecraft feature (providing a bonus for the very beginning of the game), and cargo (providing a bonus for your first base). You can even choose the geography and biome of the planet you’re colonizing, providing various aesthetic and minor gameplay changes. This adds a level of customization never before seen in the series, making your faction truly unique.

But how does it compare to Alpha Centauri? Mechanically, quite well. For all the strength of its writing, Alpha Centauri is still a good twenty years old at this point. And while it plays remarkably well considering its age, the user interface has not aged well. Beyond Earth – drawing from years of refinement to the Civilization formula – is easier to pick up and play. But plot-wise? Beyond Earth has its moments of brilliance, but is lacking in some critical areas.

The factions – or ‘sponsors’ – are largely geographical and much more grounded in nature, representing power blocs on Earth that formed in the wake of ‘The Great Mistake’. Details on what the Mistake involved are sketchy, but it’s implied to have been a regional nuclear war that rapidly accelerated climate change and sea level rise. Things more or less stabilized eventually, but the Inflection Point – a point where the situation will deteriorate and humanity will no longer have the resources to leave Earth – is rapidly approaching. As a result, the sponsors launch a series of colonization missions collectively known as the Seeding, aiming to ensure that humanity will survive even if the worst comes to pass on Earth.

A decent enough premise. It’s a lot more optimistic than Alpha Centauri – to the point where contact with Earth can be re-established – which I really appreciate. But the sponsors and their leaders don’t have quite the level of nuance as the Alpha Centauri factions. The leader quotes aren’t as intriguing or insightful, and it doesn’t help that they’re all read by a single narrator instead of distinct voice actors. While the leaders do make fully-voice and animated appearances during diplomacy, these are fairly limited and don’t really add much to their character that we wouldn’t get already.

Though that’s not to say that there isn’t some interesting writing in the the game. The backstories behind all the different sponsors are genuinely interesting, and go as far as justifying their in-game bonuses. For instance, the trade-focused Polystralia was formed by Pacific nations threatened by rising sea levels, and grew to economic prominence by being one of the few nations to double down on trade instead of going into isolation during the Great Mistake. The leaders also have some dimension to them as well. Samatar Jama Barre – leader of the People’s African Union – stood out to me in particular, leading in a very welcoming and humanitarian manner while harbouring some deep resentments about modern colonialism and mixed feelings on religion.

But while each sponsor can be said to have some sort of ideology, they don’t really them in the same way the Alpha Centauri factions did. In that game, you’d often be able to tell exactly what a faction was about based on the game alone. The Human Hive? An authoritarian collective. The Spartan Federation? Militaristic survivalists. Morgan Industries? Capitalists. So what does Franco-Iberia stand for? Or the Slavic Federation? (The preservation of Western culture and space superiority, respectively, in case you were wondering.) The sponsors still unique in terms of gameplay bonuses, but these bonuses are very minor compared to those in Alpha Centauri, and come with no drawbacks to really make the sponsors truly distinct mechanically.

Now, to be fair, Beyond Earth does pick up the ideological slack in another way. By researching certain technologies or choosing certain quest options, the player’s faction will lean towards one of three ‘affinities’. Each one is an ideology on how humanity should progress as a species: Purity wishes to preserve the past and terraform planets to suit humanity; Supremacy intends to harness cybernetics, robotics and AI to make humanity able to survive in any environment; and Harmony suggests using genetic engineering to modify humanity to fit into whichever environment it inhabits. The Rising Tide expansion pack even allows you to hybridize, such as Purity-Supremacy wanting to keep humanity pure while using robots and drones to do its bidding. Decent enough sci-fi concepts, and the fanbase has had many a debate into the pros and cons of each. But I think there could have been more done to really explore these ideas in-depth, or even tie them back to the real world. With things like environmental decline and labour automation poised as critical issues, I can definitely see the affinities reflecting them in some way.

I don’t want to make this sound like I’m ragging on Beyond Earth. It’s not Alpha Centauri 2, or Alpha Centauri: The Remake. It’s under no obligation to try and follow in its predecessor’s footsteps. I just think it’s a shame Beyond Earth couldn’t have drawn from Alpha Centauri’s strengths a little more to become something even greater. For what it is, Beyond Earth is still my favourite Civilization game and one of my favourite strategy games in general. In fact, looking back at it, I might even do a future blog post on it. Reading the history of the various sponsors was my first exposure to climate fiction, which is a genre I’ve only become more interested in since.

Eternity Lies Ahead

As for Alpha Centauri, it’s far from forgotten. It’s available on Good Old Game for a fair price, and still has an active fanbase and modding community. I’d particularly recommend checking out the blog Paean to SMAC for one fan’s philosophical musings on the game. Brian Reynolds – the main creative force behind the game – even expressed interest in a reboot earlier this year, though it sounds like there are some legal kinks that would need to be worked out first.

I, for one, would definitely like a remake see come to fruition. Given current events and issues, I feel like a lot of the ideologies in Alpha Centauri are actually more relevant today than they were in the 90’s. The environmentalism of the Gaians takes on a whole new degree of importance with the increasing prominence of the climate crisis. Resurgent authoritarianism and the rise of China as a superpower makes the Human Hive eerily prescient in some ways. Factions like the Lord’s Believers and the Cult of Planet show a degree of religious extremism that seems worryingly commonplace. Let’s just hope we don’t have to go as far as Alpha Centauri to tackle some of these issues.

But regardless, Alpha Centauri still stands as a massive achievement of video game writing. Through creative concepts, clever delivery, willingness to dissect big ideals, and plain ol’ quality writing, Alpha Centauri reaches a level of narrative sophistication rarely seen in its medium, and rarer still its genre. This makes it a more than worthy addition to the annals of science fiction, and a fun piece of entertainment to boot.

Well put together review! I’m a huge fan of the game buying it on release and still play it to this day here and there. Simply a brilliant game that has stooe the rest of time and IMHO a contender for overall greatest PC game of all time.

LikeLike