In little over a month at time of writing, the highly anticipated video game Cyberpunk 2077 will be released. Its development has been long and storied, from frustrating release delays to the surprise casting of Keanu Reeves as ‘rockerboy’ Johnny Silverhand. But the history of the game – and the genre it shares its name with – is far broader. And one of its roots goes back surprisingly far.

2077 is actually an adaptation of the tabletop roleplaying game Cyberpunk, first released in 1988. Drawing its name from a term coined by writer Bruce Bethke in a 1983 short story of the same name, Cyberpunk depicted a technologically sophisticated world wracked by greed, inequality and disaster. It’s a setting where ‘netrunners’ with brain-machine interfaces traverse the Net for secrets that corporations would kill to protect, while clans of ‘nomads’ roam the highways like particularly dedicated Mad Max cosplayers. Indeed, this represents a fairly archetypal ‘cyberpunk’ setting; one typified by a disrupted social order alongside – if not outright exacerbated by – advances in technology. The genre came into its own in the 80’s, seeing the release of such tent-pole titles such as Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner (based on Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), Katsuhiro Otomo’s manga (and subsequent anime adaptation) Akira, William Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy (particularly the novel Neuromancer), and – naturally – Mike Pondsmith’s tabletop RPG Cyberpunk.

But there’s a novel that predates these titles that depicts a similar future: a vision of a futuristic Paris that is still very much the city of lights, if only because of the electric lights that illuminate the soaring buildings. There is no room for the romanticism that once defined the city’s past; technology and commerce reign supreme while art and literature decline. This same technology allows devices to connect across vast distances while human connections become all too rare. And, of course, the music is electronic.

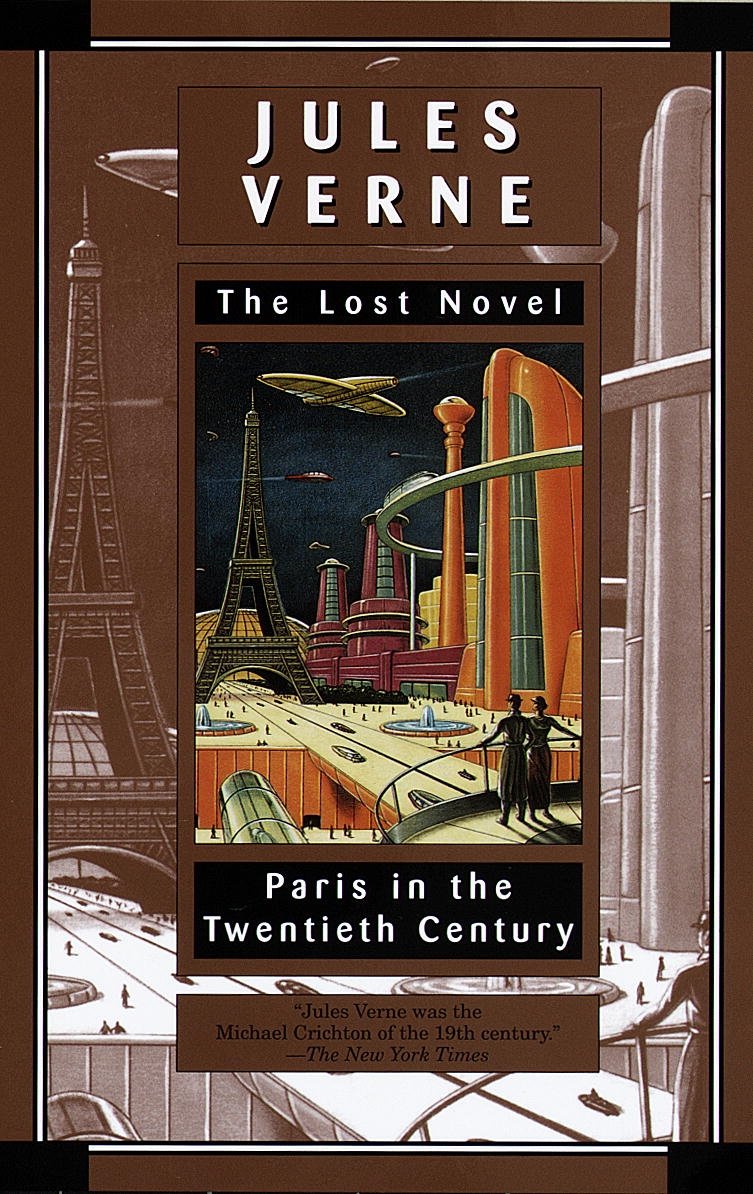

Doesn’t sound too far-fetched, does it? Fairly typical for a cyberpunk setting. Not too far removed from our own society, even. But you must consider that this novel – Jules Verne’s Paris in the Twentieth Century – was written in 1863.

The name Jules Verne will likely be familiar to fans of steampunk – one of many derivatives of cyberpunk, focusing on 19th century industrialism instead of more recent technologies. Many of Verne’s works were encapsulations of the scientific idealism of the Victorian Age, highlighting what wonders might be possible through science. Robur the Conqueror centered around the plausibility of heavier-than-air travel years before it took off, so to speak. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea depicted a submarine far beyond the capabilities of the primitives submersibles of the time. Even From the Earth to the Moon – famously adapted into A Trip to the Moon by early filmmaker Georges Méliès – proposed the idea of space travel well before it became a tangible reality. Accuracy of Verne’s visions varied, of course. For instance, From the Earth to the Moon correctly identified Florida as the launch point for a lunar mission, albeit one that fired a capsule out of a gigantic gun in a very literal moonshot.

But Paris in the Twentieth Century stands head and shoulders above the rest of Verne’s work in the accuracy department. It’s depiction of 20th century Paris – set in the 1960’s specifically – is truly remarkable given that many of the technologies present were either in their infancy at the time he wrote it, or simply did not exist at all. TV Tropes has a nice, digestible list of what Verne got right here. To provide a summary of some of the biggest standouts, Verne managed to predict:

- Automobiles resembling the modern car, compared to the obscure and experimental ones of the time.

- Advanced electro-mechanical calculators not entirely unlike early computers.

- Telecommunications, both with the aforementioned calculators able to transmit data over large distances and the existence of ‘picture-telegraphs’.

- Modern architecture and city planning, depicting skyscrapers and suburbs (albeit in a way that resembles pretty much any modern major city except Paris).

- Mutually-Assured Destruction, with the threat of devastating weapons of war leading to an uneasy stalemate between nations.

- Hippies.

- Much of modern music, including genres such as electronic, heavy metal and punk rock, alongside the decline of live classical music, the rise of recorded music, and the emergence of an artsy underground. There are even music-creating machines akin to synthesizers.

- Climate change, in a way. This isn’t on the TV Tropes list, but towards the end of the novel an unprecedented winter unleashes mass famine and illness across Europe. While not necessarily realistic, it is a reminder that – for all our technologies – we will always be at the mercy of nature.

Much of this list alone already resembles the late 20th century of our world, which proved fertile ground for the cyberpunk genre. But what truly links Paris in the Twentieth Century to the genre is the plot. It follows a young man named Michel Dufrénoy, who graduates with a degree in literature into a world that places increasingly little emphasis on meaningful culture. While he does find some tolerable work as a bookkeeper, he is still alienated by most of his family for his choice of study and eventually finds himself involved in the underground art scene. But this does little to change the world around him. And as he loses his job and is forced to rely solely on his artistic merits to survive, it isn’t enough to save him.

Consider the word ‘cyberpunk’ for a moment. ‘Cyber’ is generally used to relate things to computers and related technologies, while ‘punk’ is a movement with a set of staunch anti-establishment, pro-individualism beliefs. While specific ideologies can vary, many cyberpunk protagonists do fall into the category of cultural rebels, often ‘sticking it to the man’ by fighting against greedy corporations and corrupt governments. Indeed, if you look at the above links to the Cyberpunk Wiki, you’ll see that anti-authority attitudes are a common theme in the description of various character roles. And as an underground artist rejecting the prevailing social attitudes of his time, Michel Dufrénoy is easily something of a punk, at least by Victorian standards.

And yet, the world he inhabits is actually a lot closer to the cyberpunk genre than the more Victorian-esque steampunk in terms of technology. Verne predicted that steam power – the driving technology and very namesake of steampunk – would not be the fuel of the future, instead depicting compressed air and electric motors as the main energy sources. And while the ‘computers’ of the setting are far from what a typical cyberpunk setting depicts, the technology that Michel is surrounded by and interacts with means he may well be the ur-example of a cyberpunk protagonist. If he were to be transplanted into a more traditionally cyberpunk setting it wouldn’t be hard to envision him as a bona-fide rockerboy.

Admittedly, Michel’s life as a starving artist in a fanatically commercialized world hits a little close to home, though I don’t think modern society is quite as bad on the cultural front as Verne’s vision. Much of that is likely Verne’s own cynicism talking. He himself spent many years as a stockbroker, despite hating the job. That would certainly explain why Michel’s employers and businessmen in general receive such a negative depiction. But cynicism about the future is a surprisingly common element of Verne’s writing, especially in his later years. Master of the World – a surprise sequel to Robur the Conqueror – has the titular Robur going from a mischievous but idealistic inventor to a violent extremist aiming to forcibly bring about an end to war. Interestingly, Michel also shares a name with Verne’s real-life son, with whom he had a rocky relationship. However, Michel Verne was born in 1861, a mere two years before Paris in the Twentieth Century was written. It could just be coincidence, but Verne’s own father is known to have disapproved of his desire to become a writer. Perhaps Verne feared what might happen if his son followed in his footsteps in what he saw as a culturally-devoid future. One can only speculate.

Whatever the case, Verne never lived to see Paris in the Twentieth Century‘s publication. The novel was turned down multiple times during his lifetime for being – I kid you not – too unrealistic. After Verne passed away in 1905, the manuscript sat in a safe before being uncovered in 1989 by Verne’s great-grandson. It was ultimately published in 1994 (with an English translation from its native French coming two years later) to genuine fanfare, being hailed as the lost work of a great writer. Critic Evelyn C. Leeper even pushed for the novel to win the 1996 Hugo award, though sadly that didn’t materialize.

Hugo or no, Paris in the Twentieth Century remains a phenomenal novel in what it accomplished. It’s a testament to Verne’s imagination as much as his grasp of science, and perhaps some prescient insight he held into human nature. He created a setting and plot that strongly resembles not only a genre that wouldn’t emerge for another century, but also reality itself in an eerie number of ways. And considering how this same vision was repeatedly rejected by others during his lifetime, Jules Verne may well have been a punk in his own right.